Paul of Tarsus: Our Guide in Faith

If God is for us, who can be against us? … I am convinced that neither death nor life … will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Saint Paul’s Letter to the Church in Rome (Chap 8; vv31, 38, 39)

There can be little doubt that Paul has had more influence over the development of Christianity than any other person. His writings are the oldest Christian records. They give us a sense of the challenges facing the followers of Christ immediately following the Resurrection. They cover a huge range of issues including most of those studied by later theologians, and many that remain intensely topical, such as the relationship between partners in marriage and the foundational importance of love and charity.

However the thing that most sets Paul and his letters apart from the rest of scripture is the force of his personality and the immediacy of his writing. His letters give an extraordinary sense of this person, his passion and commitment. We can feel that we know him to a greater extent than anyone else in the bible.

So it’s very appropriate to take Paul as the starting point and guide during this exploration of our faith tradition. But in doing so we shouldn’t be naïve and assume that he has the answer to every question, or that everything he said will be immediately meaningful to us – after all he was writing 2000 years ago.

As we will throughout this book, we’ll start by setting a context for Paul’s work to help us relate to a time very different from our own. We’ll review what we know of his life, recognizing that there is much that is unknown. We’ll finish by considering some of the major ideas that emerge from Paul’s letters and have continued to influence thinking in the church for those 2000 years.

The world of St Paul

We’ve already noted that Paul’s letters are the earliest writings we have from Christian sources. Dating old documents is a challenge and there remains debate about when exactly Paul’s letters were written, and even the order in which they were produced. However is seems likely the earliest are from about 50-60 AD, roughly 20 years after Jesus’ death, and they predate the Gospels (as we know them) by at least 25 years.[1]

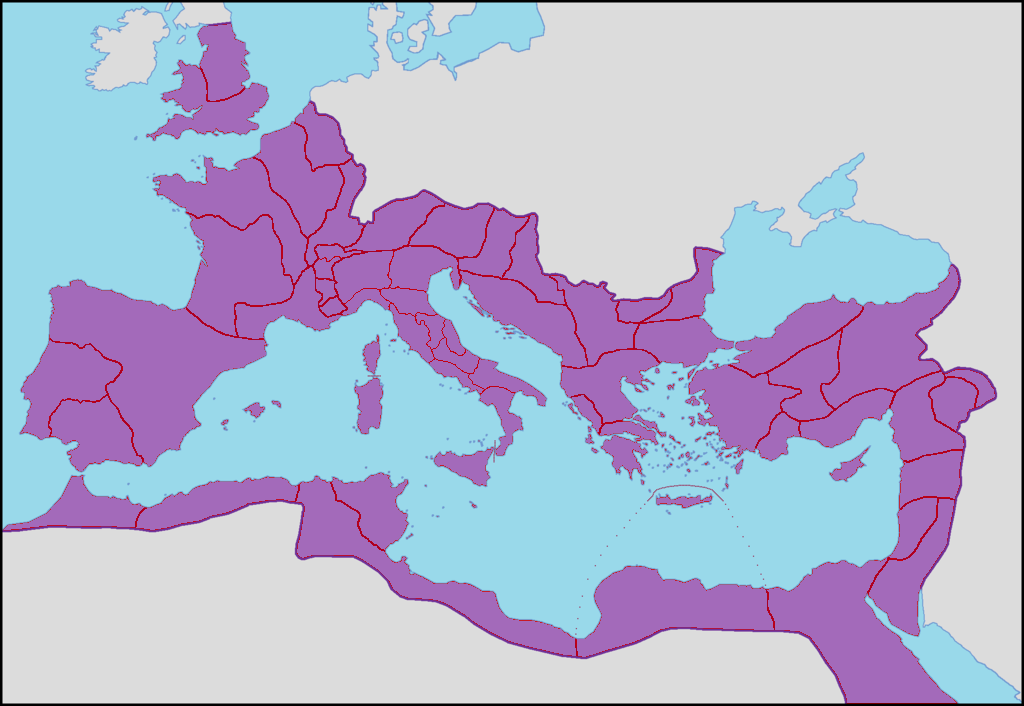

From a historical and theological perspective the importance of Paul’s writing is not just that it is the earliest Christian record, but that it reflects clearly the intersection of Jewish, Roman, Greek and Christian ideas that was present in the earliest days of the church. The Roman Empire of Paul’s time was highly cosmopolitan. In Paul we see the formation of the melting pot of ideas, philosophy, and worldviews which has continued to feed Christianity until our own time (despite, one might note, the efforts of many throughout its history to limit church traditions to one or other preferred perspective).

The Roman Empire of the first century was also a very pluralist society, more so than any other (at least in the Western world) until the late 20th Century. The peace of Augustus which followed the collapse of the Roman Republic (in 27 BC) led to the creation of a state which survived for another 400 years in the west and 1400 years in the east (despite the well known personal failings of many Emperors).

This empire accommodated a huge diversity of peoples, languages, customs, and social mores – ranging from extreme licentiousness to extreme asceticism. Key to maintaining cohesion while accommodating this diversity was a large degree of local autonomy, and minimal central regulation backed by a totally dominant military force. At all levels from the personal to the “international” there was an expectation of the use of extreme violence to maintain social control (crucifixion was routine both in conquest and as a civil punishment).

The Empire in Paul’s time embedded a division between the Greek east, evolved from the earlier civilization of the Grecian peninsula, and the Roman west. It would indeed separate back into these parts following the time of Saint Augustine, 400 years later.[2] The Roman tradition provided the social and economic structure, and the military prowess, but the culture was dominantly that of Greece. All educated people spoke Greek, and Greek was the language of all serious intellectual debate. We see this reflected in Paul where he clearly identifies his positions relative to Roman social structures, but to Greek ideas and philosophy (and he wrote in Greek).

Judaism was something of an anomaly.[3] The strongly uniform and traditionalist Jewish society in Israel was very untypical of Roman provinces, which normally assimilated a much more Roman lifestyle (even in such remote places as Britain). Jewish monotheistic beliefs were tolerated, although considered bizarre in the extreme. Even before the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70, it is likely that many more Jews lived outside Israel than within it. Jewish communities typically contained substantial numbers who had converted to Judaism, or who associated themselves with Judaism even if not being converts (which required circumcision and strict observance of the dietary laws – the former often being considered more of an impediment than the latter). These communities outside of Israel were the primary focus of Paul’s mission.

Paul, the man

What of Paul himself, the person we so readily encounter in his letters? His passionate humanity and concern for those he considers his responsibility is obvious. The passion can descend even to cruelty in defense of his flock: For in Christ Jesus, neither circumcision nor uncircumcision counts for anything, but only faith working through love… Would that those who are upsetting you might also castrate themselves! (Gal 5:6,12).

He is often considered the first theologian, and certainly his ideas have had enormous influence on theological thinking from St Augustine to Martin Luther, and on many recent theologians, Catholic and Protestant alike. However his intent in his writings was not at all to provide a systematic exposition of Christian faith and belief. Like his Lord and master he saw himself as a pastor, telling people what they needed in their particular situation in order to understand the way God was working in the world. His letters are all written to particular groups for very specific purposes. Even the most systematic is one he wrote introducing himself, before his arrival, to the Christian community in Rome.

We can also see in his letters the development of his own thinking and understanding as he worked at the mission he saw as having come directly from Jesus. This sense of mission and purpose is perhaps the most striking thing in the letters – if ever there was a driven personality it has to be Paul. The basis of this mission however is obscure. Paul never met Jesus and in the period after Jesus’ death was a strong supporter of the pharisaic Jewish movement to suppress the sect of Nazarenes (as followers of Jesus were called at that time – the term Christian came a little later). The account of his conversion on the road to Damascus is well known. Paul himself provides only the briefest of descriptions of this experience in his letter to the Galatians. There are slightly fuller and varying accounts in different contexts in the Acts of the Apostles. Regardless of the specifics of this event, what is very clear from Paul is that he understood himself to have been in direct communication with Jesus, in a way which gave him equivalent authority to those who accompanied Jesus during his earthly life:

We might find it more helpful to consider Paul as the first (Christian) mystic rather than the first theologian. Much of his writing is concerned with the nature of the human relationship with God through Jesus – both his own relationship and that he wants for those he has converted:

This language has much in common with that of later mystics who focused their attention on an individual, intimate relationship with a living God who was present to them in the center of their daily reality. We see exactly this also in Paul.

Whatever lens we prefer, it is futile to attempt to place Paul into a single category, theologian or mystic, radical or traditionalist, particularly with categories that only came to be recognized centuries later. He was by any measure unique and we should seek to benefit from the range of his experience and wisdom as our guide to faith.

Our sources for information about Paul

Alongside Paul’s letters, the Acts of the Apostles is for the most part an account of Paul’s missionary activities. These sources do not completely agree in respect of what we would consider factual information, for example there are irreconcilable differences in the chronology of some of Paul’s activities as reported in Acts and as implied by his letters. We also speak glibly of “Paul’s letters”, but it not certain that all those traditionally attributed to Paul were written by Paul himself, some are fairly clearly incomplete, and others may be composites created by later editors.

However this situation should not unduly concern us. We are not looking to Scripture for a historical reconstruction of past events, we are seeking an understanding to guide our present lives. While many early Christians considered that the Letter to the Hebrews was Paul’s work, we can now accept that this is not so, and that we get greater benefit from it by recognizing the different content and assumptions it used from those we find in Paul’s writings[4]. Regardless of scholarly debates about sources and texts, we can take value from Paul’s words as they come down to us, whether they originated in something he wrote himself, something that was edited by one of his followers, or that was written in his spirit.

We should also confront the question of what actually was his name. Sometimes (in Acts) he is referred to as Saul. In his letters, he always refers to himself as Paul. Some have wondered if there is some significance associated with an apparent change of name, similar to that when Jesus names Simon as Peter[5]. In fact the explanation is much simpler – in a multi-lingual society people often had apparently different names. In this case Saul was his name in Hebrew and Paul (or Paulus) in Latin.

The life of St Paul

Paul was born about same time as Jesus, in the ‘free’ Greek city of Tarsus, in what is now eastern Turkey. The city was free in the sense that as long as no trouble occurred it was locally governed without imposition of direct Roman control. It was typical of many eastern cities, and had a significant Jewish population, some in positions of prominence. Paul’s father was a Jew but also a Roman citizen. This status would have been relatively uncommon, both for the local population in general and particularly within the Jewish community. Roman citizenship conferred significant rights in the case of conflicts with the civil authorities. Paul took advantage of this later in his life.

Paul had a trade, possibly as a tent-maker, but he wasn’t brought up to practice it. We might think of him as white collar but not aristocratic in status. His family must have been fairly wealthy because he was able to adopt a career which was part religious and part academic. He was trained in the pharisaic tradition of interpreting the Mosaic law, and became a traveling rabbi – in a way rather like Jesus, but with a somewhat different agenda.

Our knowledge of Paul’s biography starts with his appearance in Acts as the presider over the execution of Stephen, who had been appointed as one of the first assistants of the apostles. Saul is a leading member of the mainstream Jewish tradition which saw the followers of Jesus as heretics (just as they had viewed Jesus himself):

After the death of Stephen, Paul’s leadership of the persecution continued as he headed to Damascus.

At this point he is unexpectedly interrupted. The ferocity of Jesus’ intervention matches that of God’s call to any of the prophets in the Old Testament – this is not gentle persuasion, more a slap in the face: Saul, Saul why are you persecuting me! (Acts 9:4) The fact that the account is repeated three times in the Acts of the Apostles indicates that it was seen as very significant by the early Church. It’s also very clear that the early community of Christians found it hard to accept this conversion – given the extent of the turn-around, we can hardly be surprised by this.

Following his dramatic conversion, he then travels to Jerusalem, meets the apostles, and starts causing more trouble – now by arguing for the Christians against everyone else. It seems the early Church found his involvement unhelpful and they sent him back to Tarsus, maybe for his own protection or maybe for theirs. Acts immediately notes: The church throughout all Judea, Galilee, and Samaria was at peace (Acts 9:31). It seems that Paul was never easy to be around!

There are different chronologies in the Acts of the Apostles for the time following his experience on the way to Damascus and that Paul himself gives in his letter to the Galatians. However we can determine fairly clearly the overall shape of his career and some of his activities following his conversion.

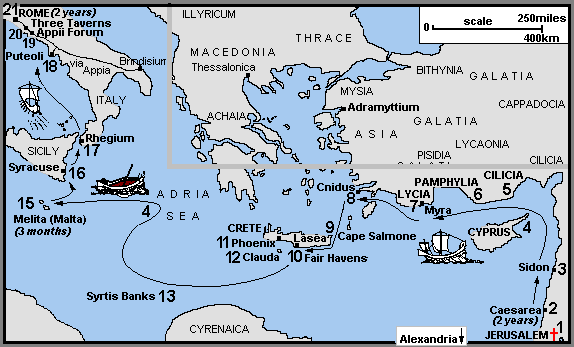

There is a period of about 10 years after Damascus for which there is no information. As best we can judge, Paul returned to his home area and was probably associated with the church at Antioch. The period for which we do have knowledge covers the time of his journeys up to his arrival in Rome about AD 60. After that again there is no record of his activities. There is no reason to doubt the tradition that he was martyred in Rome, but whether this was in the persecution of the Emperor Nero following the great fire of AD 64 or somewhat later we do not know.

The Acts of the Apostles concentrates on the series of great missionary journeys that Paul undertook, and his letters cover the same period. These journeys are remarkable for their rigor. Even today traveling these routes is strenuous. Paul traveled the region from Israel to Rome at least three times[6] covering over 2000 miles – on foot. Of course Paul was not unique in this, another great traveler in later times was Saint Ignatius, founder of the Jesuits, who covered a comparable distance – in his case passing through battlefields in a time of war.

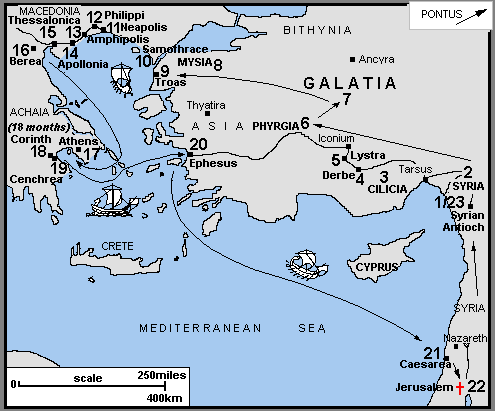

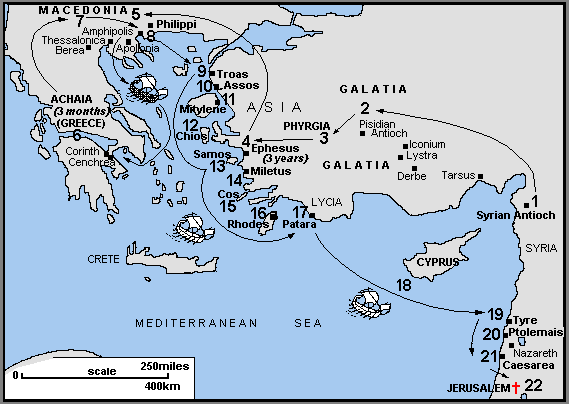

The first journey was relatively local, covering Syria, Cyprus and Asia Minor, a mere 625 miles. This was in about AD45.

The second covered a huge area of Asia Minor, Macedonia, and Greece during which Paul travels about 875 miles. In the scriptural narrative Paul meets the Roman governor in Greece during this journey. We can identify this person in other historical sources and be confident that the date was around AD 52. During this journey he spent about 18 months in Corinth, a place significant in his later correspondence.

The third journey covered a similar area and included 3 years in Ephesus.

Paul does mention the possibility of a journey beyond Rome to Spain (in Romans 15:24). Some other early Christian writers mention this journey but there is no direct evidence it ever occurred. It is possible that his trip to Rome from Jerusalem, after he invoked his right as a citizen to trial there, was his final journey. It is certainly the last time we hear from him.

Before we turn to Paul’s ideas and their importance for our faith today, we should note one final historical fact. Paul’s activities dominate the account of the early church provided in the Acts of the Apostles, but he was certainly not the only Christian missionary at that time. Paul himself sometimes refers to others, often in rather unflattering terms, in his letters. More significantly, the churches in Damascus and Antioch were already established before Paul started his work, since that was where he went initially following his conversion. The church in Rome was well developed before Paul went there since he writes to an established community which only knew him by reputation. Perhaps most importantly, the church in Alexandria, Egypt, the epicenter of intellectual life in classical times had no connection with Paul at all.

We have no record of these other early missionaries, except for later accounts which were almost certainly created to fill the gaps in the historical record[7]. However when we come to consider the later history of the church we need to recognize that it had diverse roots from the very beginning. Despite his importance, the church did not arise from Paul’s sole efforts. This also refutes the tendentious claim that Christianity was founded by Paul rather than Jesus, with Paul taking a Jewish tradition and making it into something alien and divorced from Jesus’ teaching.

With that rather silly idea put to one side, let us now consider what Paul did contribute to our faith, and the power it still has for us after so many years.

Paul’s teaching

Given that Paul’s ideas are so diverse and unsystematic in his letters, it is difficult to provide a brief and adequate overview. What follows addresses three questions that were clearly crucial for Paul and are of enduring importance for us.

First, who was Jesus? As we might say, who was this guy, and why did/does he matter so much? Paul wanted to answer this question for himself and for others. Second, and closely related: what did Jesus do for us? Finally, the one that was perhaps most central in Paul’s thinking: what do I have to do or become as a result of a relationship with this Jesus? In modern language, the “so what” or “bottom line”.

Who was Jesus?

Paul addressed this question primarily in a Jewish context – how did Jesus relate to the plan of salvation which God had revealed in and through his people Israel? The debate about Christ’s nature in terms of humanity and divinity, as it led to the Creeds, came later and grew out of Greek philosophy.[8] That was not Paul’s starting point.

Paul links Jesus to the Hebrew prophecies and sees his resurrection as the culmination of those prophesies and the primary evidence of his status: …the gospel of God, which he promised previously through his prophets in the holy scriptures, the gospel about his Son, descended from David according to the flesh, but established as Son of God in power according to the spirit of holiness through resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord. (Rom 1:1-4). We should also note that this perspective is not unique to Paul – it was the perspective of the early Church as described in the words of Peter and Stephen, also in Acts[9].

While Paul positions Jesus very clearly in this Jewish context, he is also at pains to emphasize that God’s relationship to humankind is changed by Jesus. This relationship is not based on following rules laid down by God, the Law revered by the Jews. The relationship was a personal one, not a legal or cultural one[10]. The person on the other side of this God-human relationship is Jesus: But now the righteousness of God has been manifested apart from the law, though testified to by the law and the prophets, the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ for all who believe. (Rom 3:21-22).

This is where Paul’s distinctive perspective begins to emerge. His inclusiveness in proclaiming that the relationship offered by God through Jesus was not only for Jews was not new (it is very clear, for example, in Isaiah) but it was very much out of line with the then current Jewish (and Christian) perspective. The major debate on this point is spelt out in Acts: Some who had come down from Judea were instructing the brothers, “Unless you are circumcised according to the Mosaic practice, you cannot be saved.” Because there arose no little dissension and debate by Paul and Barnabas with them, it was decided that Paul, Barnabas, and some of the others should go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and presbyters about this question. (Acts 15:1,2)

So Jesus’ message as delivered by Paul reflects and embodies the radical inclusiveness of God’s relationship with His creation. But what does that mean for Jesus himself – the person Jesus – is he “just” another prophet communicating an understanding of God? That position would be easy to understand and appreciate for Jews and non-Jews.

Paul, again in common with the early church, doesn’t believe this is an adequate reflection of Jesus’ nature and power. At the beginning of his letter to the church in Colossae, Paul quotes what is probably an existing hymn which sets out the extent of the claim made for Jesus: He is the image of the invisible God … in him were created all things in heaven and on earth … He is before all things, and in him all things hold together … (Col 1:15-17) This identification between Jesus and “the invisible God” was immensely challenging for Jews who had fought, both literally and spiritually for centuries, to defend the distinctness of the divine and the human. At the time of Paul it was particularly problematic since the Roman emperors declared themselves as divine – so the idea of a “god-man” was in no way strange to classical thought. The divinity of the Roman emperor was abhorrent to Jews but also to Christians. This sort of divine status was certainly not what Paul and the early church were trying to claim for or about Jesus. Figuring out what this Jewish/Christian view of the ‘God-man’ did mean in terms of Roman and Greek ideas would take about the next 400 years.

What did Jesus do for us?

We can relate easily to the idea that Christ loved us, at least if we think of it purely by analogy to love between humans; perhaps not so easily to the fact that he sacrificed himself for us. For us, the idea of sacrifice is familiar in the context of parental responsibility or military combat. On the other hand, the sense in which Paul uses the term “sacrificial offering” is closely tied to the tradition of Temple worship which was central to Jewish life in his time, but is not so close for us.

Paul expresses himself even more directly when he says: For I handed on to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures (1 Cor 15:3). Here the challenge is clearer – what does it mean to say “Christ died for our sins”?

Paul explains this by linking sacrifice with his ideas about grace, faith, and justification (a Roman legal term): … all have sinned and are deprived of the glory of God. They are justified freely by his grace through the redemption in Christ Jesus, whom God set forth as an expiation, through faith, by his blood (Rom 3:23-25)

This is one of the areas where Paul’s thinking is most complex and has been the foundation of both great theology and devastating arguments, notably in the hands of Luther.[11] Despite the difference from Paul’s context of Temple worship, we can still appreciate the point of Paul’s perspective by reflecting on the analogy with the relationship between parents and children in extreme circumstances or of comrades in battle. The idea that a person would sacrifice him or herself for the benefit of someone else is not so alien to us. Even the idea that such a sacrifice would be to compensate for the faults of failings of another person is not strange. And in both cases leads back to the question of how we would / should respond to being the recipients of such a gift.

So what!

We must carry the argument to its conclusion. If we accept that Christ loved us and died for us, then what does that require of us? Do we simply say thank you and get on with life?

Paul didn’t see it as a matter of salvation followed by our recognition of the fact. It’s rather the other way round – the recognition causes the salvation: if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved (Rom 10:9). But being saved is not like a change of clothes, despite the powerful imagery of being washed clean. Paul knew from his own experience that he’d been changed, fundamentally, by his meeting with Jesus – and he believed that the same was true for anyone who entered into that relationship with the living Christ.

Of all the “life changing” experiences we could imagine, this one is the most profound – we become, literally, different people: How can we who died to sin yet live in it? Or are you unaware that we who were baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were indeed buried with him through baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might live in newness of life. (Rom 6:1-4) This is an incredibly powerful idea and has layers that we are still uncovering today as our understanding of human nature is enhanced by study of everything from psychology to anthropology to genetics.

The conduct of a Christian reflects this new identity: Now those who belong to Christ have crucified their flesh with its passions and desires. If we live in the Spirit, let us also follow the Spirit. (Gal 5:24-25) The key ingredients in this change are the famous triad: Faith, Hope, and Charity (Love)[12]. The consequences are the longer list: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control[13]. Even after almost 2000 years this still seems a pretty good value proposition!

Questions for Consideration

Footnotes (Click footnote number to return to text.)

[1] see Studying Scripture: Texts and Interpretation

[2] see Saint Augustine of Hippo

[3] see Studying Scripture: Bible History

[4] Perhaps the most notable difference is the emphasis in the Letter to the Hebrews on viewing Jesus and his importance from the perspective of Jewish temple tradition, with frequent comparisons between Jesus and the High Priests. Paul’s letters speak from the perspective of the Jewish diaspora spread through the Empire, with very little reference to traditional Jewish practices in Jerusalem.

[5] Matt 16:18

[6] Paul’s letters provide information for three visits to Rome, Acts talks of five.

[7] Modern textual analysis makes us much more adept at finding out what materials are likely to be ‘genuine’ or contemporaneous with the events described, versus those which have been added by later authors. We may share their frustration at the gaps, but are less likely to be sympathetic to attempts to fill them in.

It might be worth noting that this is a very modern attitude. Traditionally, filling in gaps, whether in old texts or old buildings, was considered perfectly normal and respectable.

[8] see Church History: The Patristic Period

[9] Peter quotes the prophet Joel and the Psalms in his first speech after Pentecost setting out the Christian claim for Jesus as the Messiah.

Stephen references the history of Israel from Abraham, through the Exodus, to the Babylonian exile, in his critique of his Jewish persecutors (Paul included).

[10] We might note that in the subsequent history of Christianity there has often been a strong tendency for religious practice to revert to being a legalistic or cultural phenomenon – either following the rules, or fitting in with social attitudes. Paul’s focus on the personal relationship with Jesus can be a useful antidote to such trivialization.

[11] see Church History: The Reformation

[12] 1 Cor 13:13

[13] Gal 5:22,23